In the course of World War II the Japanese advance in the Asia-Pacific in late 1941 and early 1942 was one of the most dramatic periods of conquest in modern military history.

In just five months Japanese forces occupied territory that stretched from British Burma (now Myanmar) in the west to the American Wake Island in the east.

After many campaigns the Japanese thrust was stopped and turned back. The shipping lanes through the Malacca Straits off Malaya were blocked by Allied submarines. This resulted in the Japanese supply lines being cut off.

In order to reduce the requirement for naval escorts the Japanese therefore decided to construct a railway connecting their frontline in Burma with Japanese forces and supplies in Thailand and Malaya. In keeping with the goal of freeing up resources for other fronts, the Japanese military decided to use prisoners of war and local labour to build this railway.

The Thai–Burma railway (known also as the Burma–Thailand or Burma–Siam railway) was built in 1942–43. Its purpose was to supply the Japanese forces in Burma, bypassing the sea routes which had become vulnerable when Japanese naval strength was reduced in the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway in May and June 1942. Once the railway was completed the Japanese planned to attack the British in India, and in particular the road and airfields used by the Allies to supply China over the Himalayan Mountains.

Aiming to finish the railway as quickly as possible the Japanese decided to use the more than 60 000 Allied prisoners who had fallen into their hands in early 1942. These included troops of the British Empire, Dutch and colonial personnel from the Netherlands East Indies and a small number of US troops sunk on the USS Houston during the Battle of Java Sea. About 13 000 of the prisoners who worked on the railway were Australian.

When this workforce proved incapable of meeting the tight deadlines the Japanese had set for completing the railway, a further 200 000 Asian labourers or rōmusha (the precise number is not known) were enticed or coerced into working for the Japanese.

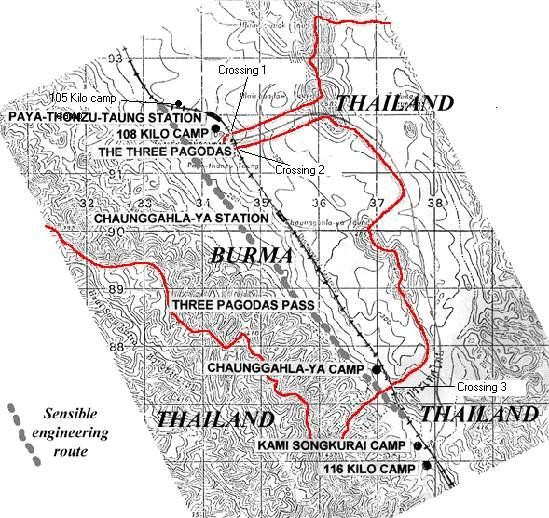

The 415-kilometre railway ran from Thanbyuzayat in Burma (now Myanmar) to Non Pladuk in Thailand. It was constructed by units working along its entire length rather than just from each end. This meant that the already difficult problems of supply became impossible during the monsoonal season of mid-1943.

Starved of food and medicines, and forced to work impossibly long hours in remote unhealthy locations, over 12 000 POWs, including more than 2700 Australians, died. The number of rōmusha dead is not known but it was probably up to 90 000.

Between October 1942 and 16 October 1943, some 200,000 Asian labourers and 60,000 Allied prisoners of war built the 415-kilometre Thai–Burma railway to supply the Japanese forces in Burma, bypassing sea routes made vulnerable when Japanese naval strength was reduced in the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway in 1942.

Once the railway was completed the Japanese planned to attack the British in India, and in particular the road and airfields used by the Allies to supply China over the Himalayan Mountains.

Begun in October 1942 and completed on 16 October 1943, the railway stretched 415 kilometres between Nong Pladuk in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Burma (now Myanmar).

A rail connection between Thailand and Burma had been proposed decades before World War II. In the 1880s the British had surveyed a possible route but abandoned the project because of the challenges posed by the thick jungle, endemic diseases and lack of adequate roads.

The Japanese also carried out a survey in the 1920s and, after completing a further survey in early 1942, decided in June to proceed, using the large workforce of Allied POWs now at their disposal. At this time Japanese engineers were assisted by small numbers of prisoners marking and roughly clearing the route of the railway.

The railway was to be constructed by units working along its entire length rather than just from each end.

The terrain the railway crossed made its construction very difficult. However, its route was not entirely the dense and inhospitable jungle of popular imagination. At either end, in Thailand and Burma, the rail track travelled through gentle landscape before entering the rugged and mountainous jungle on the border between the two countries.

When the track reached Wampo, about 112 kilometres from the Thai terminus, it started to meet jagged limestone hills, interspersed with streams and gullies. During the monsoon season, the land became waterlogged and unstable. This posed problems for construction as well as for transport and supply.

The Wampo viaduct, constructed early 1943, consists of a series of trestle bridges following the curve of a sheer limestone cliff which falls into the Kwae Noi below. The viaduct is still used today and maintained by the State Railway of Thailand. It has, however been extensively repaired and the overhang appears to be unstable.

As far as possible the railway track proceeded at a gentle gradient, as steam trains could only climb a slight incline. Where the railway met unavoidable hills, cuttings were dug to allow the line to proceed. Often the line emerged from a deep cutting onto a series of embankments, and bridges. In all, 688 bridges were built along the railway. In addition, over sixty stations were built to allow trains to pass one another, as well as refuelling and watering points.

More than 60 000 Allied prisoners of war were employed in the construction of the Thai–Burma railway, including British Empire troops, Dutch and colonial troops from the Netherlands East Indies and a smaller number of US troops. About 13 000 of the prisoners were Australian.

In addition, the Japanese enticed or coerced about 200 000 Asians labourers (rōmusha) to work on the railway. These included Burmese, Javanese, Malays, Tamils and Chinese.

Over 12 000 Allied prisoners died during railway construction, including more than 2700 Australians. Around 1000 Japanese died. It is difficult to determine how many rōmusha died, as record keeping was poor. The number is estimated to be between 75 000 and 100 000.

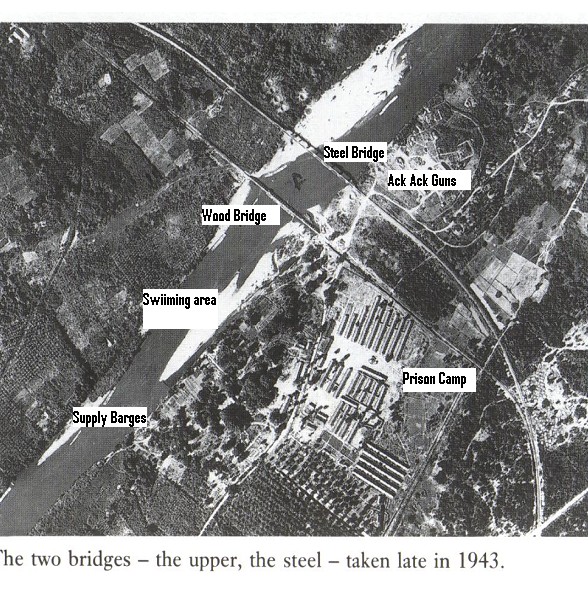

Despite being repeatedly bombed by the Allies, the Thai–Burma railway did operate as a fully functioning railway after its completion. Between November 1943 and March 1944 over 50 000 tonnes of food and ammunition were carried to Burma as well as two complete divisions of troops for the Japanese offensive into India. This attack, one of their last, was defeated by British and Indian forces.

As the railway was used to support the Japanese in Burma until the end of the war, prisoners of war and rōmusha continued to work on maintenance and repair tasks after the railway construction was completed.

Since 1945 prisoners of war and the Thai–Burma railway have come to occupy a central place in Australia’s national memory of World War II.

There are good reasons for this. Over 22 000 Australians were captured by the Japanese when they conquered South East Asia in early 1942. More than a third of these men and women died in captivity. This was about 20 per cent of all Australian deaths in World War II.

The shock and scale of these losses affected families and communities across the nation of only 7 million people.

Anzac Day services and enduring memories of the Railway focus on Hellfire Pass (Konyu Cutting), the deepest and most dramatic of the many cuttings along the Thai–Burma railway. Not all Australian POWs worked here in 1943.

Nor was the workforce in this region exclusively Australian. However, in recent years Hellfire Pass has come to represent the suffering of all Australian prisoners across the Asia–Pacific region.

The experiences of prisoners elsewhere were, in fact, very diverse but this website can only hint at these.